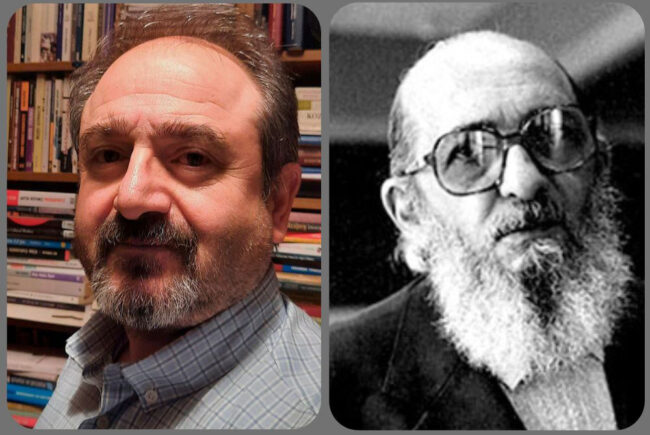

Photo: Slobodan Dimitrov and Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Slobodan Dimitrov and Wikimedia Commons

In this dialogue with the past, Hasan Aksoy, Professor of Education at Ankara University, discusses the role of Freirean education, the educational landscape in Turkey, and February’s tragic earthquake.

It is Sunday evening and Hasan Aksoy is sitting in a dim study room in his house in Ankara. “We eventually got here,” he says, smiling gently. This is our third attempted interview.

In the weeks following the earthquake in early February 2023, Aksoy tells us that the disaster has influenced everything, from daily life to the economy. It is now late February.

Hasan Aksoy is a Professor at the Department of Education Sciences at the University of Ankara, Turkey. He has scores of publications, including Hope, An Individual Memorial Note on Paulo Freire, and Teacher Authority, Autonomy, and Authoritarianism in Turkish Vocational High Schools. He has also translated several publications into Turkish, including Peter Mayo’s Liberating Praxis.

As may be evident through Aksoy’s research, he cites his significant influence as being the Brazilian educator Paulo Freire. Paulo Freire is regarded as the founder of critical pedagogy, a branch of educational praxis that positions socio-political critique and empowerment as essential to teaching and learning.

His foundational text, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968), has been enormously influential since its publication, being one of the most cited books in the social sciences. Notoriously, author and critic bell hooks stated that encountering Freire was like ‘finding water in a desert.’

Aksoy has been interested in Freire for several decades, initially drawn to the unique blend of “humanistic, revolutionary and practicable concepts.” On a more candid note, Aksoy says, “I was searching for him for my entire professional life but I didn’t realise at first how important he would be for my personal life.”

Critical literacy

Critical literacy comes from the tradition of critical pedagogy, which was directly influenced by the writings of the Frankfurt School and their Kritische Theorie. Paulo Freire, also influenced by decolonial, existential and theological discourses, developed his pedagogía crítica and critical literacy by fusing these traditions.

Aksoy explains that “critical literacy focuses on developing the student’s critical understanding of history, the economy, equality, poverty, emancipation and solidarity.” Or as Freire himself stated, “the act of cognition not only of the content, but of the why…”

“Critical literacy,” continues Aksoy, “is a part of the emancipation process, a continuous process of discerning which knowledge is being privileged within texts, and to empower students to directly address and challenge those assumptions.”

It is essential that pupils are educated how to read the world as much as how to read the words.

He continues: “engagement should be with the real world of the learners and the boundaries and barriers they face. In this process, we can see the power relations and the political nature of the things that obstruct our life, culture, language and our way of thinking.”

In his text Literacy: Reading the Word and the World (1987), written with his long-term partner Donaldo Macedo, Freire wrote that critical literacy is “one of the major vehicles by which ‘oppressed’ people are able to participate in the sociohistorical transformation of their society.”

“Education and politics cannot be separated, no education is neutral,” says Aksoy. “These are key insights from Freire. And so it is essential that pupils are educated to understand how to read the world around them as much as how to read the words. This is what critical literacy means.”

Turkey’s educational landscape

A rupture in Turkish history was the coup d’état on September 12, 1980. “This”, Aksoy says, “put a swift end to the radical and revolutionary youth movements of the 1970s and opened the way to neoliberal and neoconservative politics.”

The rise in authoritarianism and neoconservatism has created widespread issues in Turkey’s educational landscape. Explaining further, Aksoy begins to list: “big overhauls to election systems and employment methods in institutions, enormous controversies around our centrally managed exams, large discrepancies between student groups, and nationalist, neoliberal and neoconservative ideologies shoehorned into exams and curricula.”

Paulo Freire

Born in 1921 in Recife, Brazil, Paulo Freire grew up through the economic instability of the 1930s. Losing his father at a young age due to poverty, Freire forged an early solidarity with the poor and marginalised.

After studying Portuguese and Law, he entered politics, in which he focused on decreasing poverty through literacy. His political approach to literacy resulted in his incarceration and eventual exile.

It was in those 16 years of exile that he wrote some of his most influential texts. He is now generally regarded as the central figure in critical education.

“On top of this,” he continues, “the neoliberal agenda has led to the creation of many private institutions, whether that be schools, universities or places of further and technical education. These private institutions are supported by public money, while public institutions have faced cuts and decreases in quality, capacity or proficiency, for lack of funding.”

As many know, the trends Aksoy describes are not specific to Turkey. “This is the realm of Thatcher, Reagan and Kohl,” points out Aksoy, “the pioneers of the neoliberal and neoconservative politics.”

He goes on to discuss these political histories: drawing comparisons between Chile’s 1973 and Turkey’s 1980 coups d’état and describing the trends of privatisation ushered in by international fiscal foundations like the World Bank and IMF.

In Turkey’s case, “global institutions and international corporations have been taking root in educational institutions since the 1980s. Since then, wage distribution has worsened, and the educational achievement gap has risen. What we are experiencing is widespread socio-economic inequity.”

Against fatalism, towards hope

On 17 August 1999, an earthquake took the lives of around 20,000 people in Turkey. The earthquake on 6 February 2023 took the lives of more than 50,000 people.

“Some people turn to fatalism to explain things,” laments Aksoy, “and some accepted the earthquakes as godly punishments related to immoral activities. Some political figures prefer citizens to develop this belief in fatalism, as fatalism makes people hopeless and paralysed.”

“Critical literacy and critical pedagogy can help survivors question the reasons for their suffering and give them tools to help them deal with the trap of fatalism.”

The world is not finished. It is always in the process of becoming.

Writing in Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Freire states that, for justice and emancipation to take place, “a total denouncement of fatalism is necessary.”

This is part of his continuing relevance, says Aksoy, “his rejection of fatalism and his emphasis on hope.”

Aksoy claims, in line with Freire, that hope is both an “ontological need” and a “political matter”. In an ontological sense, “we see people always turning to it in times of crisis. In the face of loss, many cannot survive without it.”

In a political sense, hope is an outright rejection of the widespread “pessimism of today’s climate”, but also consciously in opposition to “blind optimism.”

“Nothing will be quickly recovered here, but it is important that there is intervention and resistance to these conditions, tragic conditions that cannot be simply seen as a natural disaster.”

Aksoy finds hope in “critical literacy as an essential tool in the struggle against these conditions, against false reporting by the mass media, against political corruption, the corruption of the emergency services, and cruel partisanship amidst the pain and ruin.”

Critical literacy, says Aksoy, “becomes the instrument through which we can overcome barriers and transcend borders.”

This is what it means to become “hopeful subjects.” It is to live in the knowledge that, to return to the words of Freire, “the world is not finished. It is always in the process of becoming.”

Author