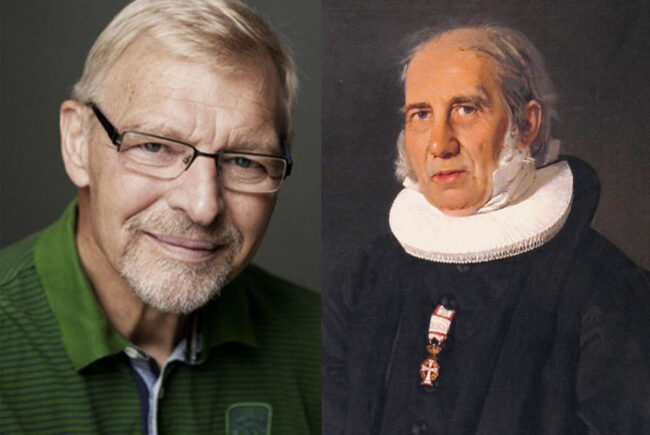

Ove Korsgaard (on the left) is an Emeritus Professor in the Department of Education at Aarhus University, and a lead expert on N.F.S Grundtvig.

Ove Korsgaard (on the left) is an Emeritus Professor in the Department of Education at Aarhus University, and a lead expert on N.F.S Grundtvig.

In this dialogue with the past, Professor Ove Korsgaard discusses N.F.S Grundtvig’s lasting influence on democratic education and the implications of ‘folk’.

Nikolaj Frederik Severin Grundtvig (1783 – 1872) is regarded as one of the most influential figures in Danish history. He was a pastor, a poet, a politician, a philosopher and a historian.

Yet he is best known to many as ‘the founder of the folk high school’, and perhaps more broadly ‘the father of western adult education’.

It could be said that Grundtvig has been in some sense canonised within Europe through the array of funding programmes, awards and foundations named in his honour. Yet his influence goes beyond the continent, a sentiment echoed in a 2016 speech by Obama, who highlighted the impact that Grundtvig had achieved globally, especially on the American Civil Rights Movement.

We spoke to Ove Korsgaard, an Emeritus Professor in the Department of Education at Aarhus University, and a lead expert on N.F.S Grundtvig. He is regarded as one of the most important interpreters of Denmark’s history, with a specific focus on democracy and folk high schools.

Korsgaard has published and edited several books and collections, including Adult Learning & The Challenges of the 21st Century (1997), The Struggle for the People (2008), Grundtvig: as political Thinker (2014), A Foray into Folk high School Ideology (2019), and Peoplehood (2022). He is currently working on yet another book about Grundtvig and the folk high school movement.

Origin of the folk high school

Grundtvig was born just before the French Revolution (1789), so his educational philosophy was closely linked to his understanding of this event.

The revolution raised a crucial question for Grundtvig, says Korsgaard.

“Why did the demand for freedom develop into a regime of terror? Grundtvig’s concern was to develop freedom free from terror or authoritarian systems. For Grundtvig, this meant ideally that the people had to be educated and formed into freedom before changing the political system”.

N.F.S Grundtvig

Born in 1783, N.F.S Grundtvig was a Lutheran minister born in the town of Udby, Denmark. Grundtvig lectured and wrote throughout his career, specifically on topics related to religion, politics and education. He embraced literature and the arts, and composed a ream of songs and poems within his lifetime. He is seen as a central contributor to modern Danish national consciousness.

Korsgaard says that the core intention behind the establishment of the folk high school was to “foster enlightenment and personal, social and political edification. It was based upon the idea of interaction as its central principle – the interaction between hand and spirit, between teacher and pupil, between past and present, between freedom and order”.

The first folk high school – or people’s high school – opened in 1844 in Rodding, Jutland. It was first in 1856 that Grundtvig became practically involved in his own school just outside of Copenhagen, but Korsgaard is quick to point out that Grundtvig’s “ideas, writing and political activity were the central driving force behind the movement from the start”.

Around 60 new folk high schools were established in the 1860s, a trend which quickly caught on in other Nordic countries: in Norway in 1864, in Sweden in 1868, and in Finland from 1889. Similarly, in the 1880s folk high schools were established in the US by Nordic immigrants.

Equal dignity in croft and castle

The folk high school cut through certain prejudices of the day, many of which were entrenched in elitist assumptions. Grundtvig’s ideas were challenging underlining societal beliefs about who can and should be educated, and who can and should participate in political processes.

Cultural edification, participation and democratic education were the origin points for Grundtvig. According to Korsgaard, he fought against the establishment of an elite democracy and regarded wider political and cultural participation as essential for popular democracy.

But it was not just a case of raising political consciousness and empowering agricultural workers. It was important that these schools also trained civic skills and practised democratic processes. This fed into many of his ideas about the state and civil society, continues Korsgaard.

Grundtvig is, beyond compare, the most influential figure in the process that transformed the conception of folk from signifying underclass to sovereignty.

“Grundtvig considered freedom and voluntariness as two sides of the same coin. Being willing to make a voluntary effort was a prerequisite for freedom as well as a popular democracy.“

However, in many contemporary educational and political discourses, democratic schools are generally on the fringes and regarded as radical; moreover, the participatory elements of the political landscape seem to be under permanent threat from a range of forces.

It begs the question of whether Grundtvig’s “Voice of the People” has lost some of its potency, and whether it has ceded territory to a reign of pessimism?

Historic-poetic as a pedagogical method

Grundtvig’s most acclaimed pedagogical method was his concept of the ‘historic-poetic’. As Korsgaard summarises, “Grundtvig saw history as essential as we cannot understand ourselves without achieving insight into the historical context of which we are a part.“

‘Poetry’ derives from the Greek word poiesis, meaning ‘creation’. For Grundtvig, creation must continue to be a possibility both for the individual and society.

“He saw this creative dimension as essential for the cultural landscape. Ultimately, history looks backwards whereas poetry – understood as imagination – looks forward,” Korsgaard says.

This was in many senses a commitment to a holistic curriculum. Grundtvig railed against ‘Schools of Death’, which he saw as being only concerned with authoritarianism, rote memorisation and learning dead languages. The fear for Grundtvig was that without the historic-poetic we risk imitation, stasis and reproduction.

Grundtvig, like many of those rooted in the Romantic tradition, were sceptical of Enlightenment thought, which often prioritised intellect over emotions.

Korsgaard is quick to say that Grundtvig’s historic-poetic should in no way exclude reason, but it is a “rejection of the form of rationalism that alone emphasises logical thinking.” It must be, in Grundtvig’s own words, ‘the great marriage: between reason and dramatic poetry’.

This has a great deal of resonance in today’s climate, where science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) have become increasingly dominant in educational discourses, often at the expense of the humanities.

In the mid-nineteenth century, Grundtvig was concerned about the hegemony of empiricism and rationalism and the effect this had on culture; in the early 21st century it seems the great marriage between science and capital has only made matters worse.

Which folk?

It is difficult to engage with Grundtvig without being wary of the violent implications of ‘folk’. It is a word that has travelled a long way and has deeply racist and nationalist connotations. The word’s inherent – or intended – inclusivity does seem ambivalent. To what extent has this ‘folk’ been truly broadened? Who is now included? And who is excluded?

Korsgaard puts forward that the word ‘folk’ has democratic connotations, and the word’s history in the Danish tradition illustrates its inclusiveness.

Grundtvig emphasized again and again during his life that we as humans participate in a continuing process of creation.

“The folk high schools created a new vision for young men and women from the countryside by distinguishing between the two concepts: ‘commoners’ and ‘folk’ understood as ‘people’. The Danish ‘folk’ or ‘people’ was used and seen as all-inclusive. Grundtvig is, beyond compare, the most influential figure in the process that transformed the conception of folk from signifying underclass to sovereignty,” he says.

Korsgaard reacts positively to challenging the racialised and nationalist currents behind Grundtvig’s ‘folk’.

“Such questioning has become central to current debates across Europe. Which individuals or groups belong to “the people”, and what does “belonging” to the people mean? Does it imply being a part not only of a national demos, but also of a national ethnos?”

Stripping Grundtvig’s nationalism of its ethnos could seem premature, given the normalisation of right-wing extremism across European discourses. As Korsgaard states, “people” as a concept will surely take on new meanings, the word itself will remain a battleground for contradicting and conflicting interests.

But it does raise an important question around which figures and symbols should be inscribed into national consciousnesses, a question which must also extend to the European Union. Are figures like Grundtvig truly inclusive? Or are they continuing a legacy and history of exclusion?

Perhaps the longevity is rooted in their ability to swing both right and left.

Reformulating civility and democracy

Grundtvig’s commitment to holistic education and civic participation are continuous recurring themes throughout the annals of adult education theory and practise.

Yet these Grundtvigian concerns seem to be at odds with contemporary educational discourse, which seem more interested in market participation than political empowerment.

But perhaps this is what makes Grundtvig’s educational reasoning around civility and democracy even more important, as it is something that needs consistent reiterating and reformulating for educators and policy-makers.

“Grundtvig emphasized again and again during his life that we as humans participate in a continuing process of creation,” says Korsgaard.

“But in order for this process not to derail, as it did during the French Revolution and in many other contexts, it requires lifelong learning understood as learning for life.“

Not for nothing is Grundtvig known as the ‘father of western adult education’.

Author