Liberal adult education has an important role in integrating migrants in Finland.

It’s 5 PM and already dark, but Juhannuskylä elementary school in Tampere is still all lit up and the doors are open. In classroom 33, a Finnish language course for more advanced speakers is about to begin, and the students are eager to share their thoughts on adult education in Finland.

“This is a good course. I have also been on a Finnish course where the teacher spoke English to us students, which wasn’t so helpful”, says Puja, who comes from Nepal and has lived in Finland for 14 years.

She has noticed that the availability of Finnish courses has become better during recent years, and discovered that the non-formal education field can offer plenty of other opportunities to study and learn new skills. “I go to yoga and photography courses. Even my children attend dancing and baking classes”, she says and laughs.

Most of the students here have lived in Finland from four to eight years and are studying or working. For them, once-a-week evening classes like this are the only option to study Finnish.

I work full-time, so the availability of evening courses is important. I want to improve my Finnish for work. I like language courses in general, and in the future I want to learn a new language – Japanese maybe.

– Mihail, Russia

Introducing migrants to non-formal adult education

This course is arranged by Ahjola, which is one of 184 adult education centres in Finland. At the moment, Ahjola has 16 Finnish courses with 297 registered students.

The number of Finnish courses has increased during the past few years, says Tuula Kivelä, head of language studies.

“We have students with diverse backgrounds and of all age groups. For example exchange students, job seekers, refugees and people who have moved to Finland because of work or their spouses”, Kivelä says.

When asked whether migrants have expressed a need for other types of courses than Finnish language courses, she hesitates.

“Not really, no. On the other hand, the liberal adult education field in Finland is quite unique, and a person coming from a different country has no idea about the variety of studies we offer”.

My mother is Finnish, so speaking the language is quite easy for me. But this course helps me to develop my writing and reading skills. I would also like to attend other courses, like life drawing. But I don’t know if such a course is available here.

– Saria, Kurdistan

Kivelä says that there is a countrywide, ongoing discussion among colleagues about just this: how can adult education centres make themselves visible to migrants? The way she sees it is that many migrants often get their first touch to liberal adult education through a Finnish language course.

“Then they can find out what else is out there. And if something else is needed, they can ask us to provide it. From our perspective, migrant students attending our open courses are just like any other students”.

From liberal adult education to civic society education

In Finland, liberal adult education institutions provide both education that is part of the official integration process, and a variety of open courses on their own initiative.

Jyrki Ijäs, Secretary General of the Finnish Folk High School Association, points out that the active role of liberal adult education in integrating migrants makes sense.

“If you look at Finnish legislation for non-formal adult education and legislation for the integration of migrants side-by-side, it’s remarkable how similar the objectives are”, he says.

These objectives include promoting equality and interaction between different groups of people, and enabling active citizenship.

Actually, Ijäs is not at all pleased with the term “liberal adult education” and prefers to use “civic society education”. “Civic society education as a term includes a reminder of the legal purpose of this education. It’s similar to the word folkbildning in Swedish”, he says.

Adult education possibilities in Finland are very good in general, especially for learning languages. I have also found a ballet for adults -course, which is a lot of fun and reminds me of my childhood.

– Natalia, Russia

More focus on language and communication

The increasing number of migrants attending open adult education courses has naturally required some changes in the operations of the education providers. At Ahjola, adding more Finnish courses has somewhat affected the overall language course availability, with the expense of foreign languages.

“And we all, including teachers of foreign languages, have had to get used to the idea that not all students necessarily speak Finnish”, Kivelä says and continues: “We also have had to think about our communication. That all information should be written clearly and be available not only in Finnish but at least in English as well”.

Recruiting new teachers to Ahjola has been fairly easy.

“We get a lot of open applications from teachers. But we operate in a university town, where a lot of teachers study and graduate. I can imagine that recruiting teachers in a more remote location can be challenging”, she says.

Towards more comprehensive and equal education

While the availability of different types of education is a good thing, dividing the expenses of liberal adult education for migrants has not been so simple.

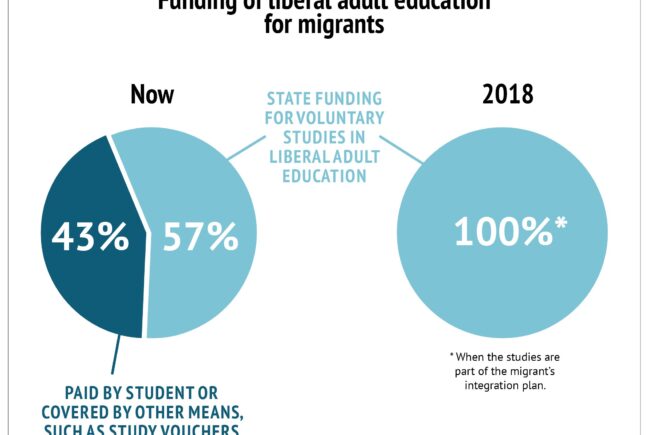

Voluntary studies in folk high schools, adult education centres and summer universities are eligible for a state funding of 57 percent. Usually the remaining 43 percent is either paid by the student or covered by study vouchers.

The pedagogic system and teachers are great in Finland. However, I’m a bit disappointed that in order to find work in Finland you have to speak perfect Finnish. It could be a bit more open-minded than that.

– Kelly, Colombia

This system is about to change, though. A bill submitted to the Parliament of Finland proposes an amendment to the legislation of non-formal adult education. If approved, liberal adult education providers will get full state funding for the education when it is part of the migrant’s integration plan, which means that the studies will be free of charge for the attendees.

From the beginning of 2018, there will also be an increased focus on teaching literacy to migrants who do not have the ability to read or write – or to do so with the Latin alphabet. Jyrki Ijäs is confident that the bill will be approved.

“I am sure of it, it’s a sensible and remarkable change. For the first time, Finland will have an education model that applies for all migrants”.

There are a lot of possibilities to learn a profession, language or find a new hobby in Finland. I read books in Finnish, but here I learn words which you cannot find in a dictionary.

– Marina, Russia

Integration and acculturation take time

The core education for migrants is language training, Ijäs says. However, learning the basics of Finnish and Swedish is not enough.

“After this, you have to acquire specific vocabulary that is necessary for academic or vocational education”.

Additionally to these kind of preparatory courses, Ijäs has noticed the need for other types of education, especially when the cultural distance between the current and previous home country is significant.

“In these cases courses on civic society and citizenship skills can be very useful. For example, knowledge of law and the principle of equality”, he says.

Integration is a long process, in which learning a new language is only the first step. Ijäs prefers to use the term acculturation, which recognizes that adaptation does not only apply to the people moving to a new country, but also natives already living there.

“Acculturation takes well over one generation. But this too fits well with the ideology of a civic society and the role of non-formal adult education”, Ijäs says.

He also emphasizes that while learning the language of the country you live in is crucial, equally important is the right to retain your native language. “According to one popular saying, a Finn stays silent in two official languages. Now think about this – what a wonderful resource it would be, if we suddenly have people fluent in 120 languages”?

More courses, more practise

Back at Juhannuskylä elementary school, the students have one by one taken time to have a chat with me during their class – in Finnish, of course. All of them find the course helpful and are very motivated to improve their Finnish skills.

Many of them are eager to move on to vocational or academic studies. The students mention several ideas for courses that would help them further develop their language skills. Learning non-formal, spoken language comes up several times, as does the wish to have more of advanced level Finnish courses available in Tampere.

“Discussion groups between foreigners and Finnish people would be very good, too”, says Marina.

It is clear that there is a need for open language courses for migrants. But as Zanna from Estonia points out, mastering the language also depends on what happens outside classrooms.

“Courses are good, but you truly learn the language only by speaking it on a daily basis, at work and with friends”, she says.

My Finnish is getting better slowly but surely. I am also studying to become a teacher of religion and want to qualify as a history teacher as well. Learning is a never-ending process, and there are plenty of opportunities to educate yourself in Finland. But if you want to build a future here, getting into working life is crucial.

– Luz, Peru