/ Photo: Silvija Einola

Life in India is changing from a traditional family-focused to more urban, work-orientated, which can cause burn-outs and rising levels of anxiety. Adult education could bring relief to the situation, but many obstacles lie ahead.

Bharti Manoj is 21-year old girl from Delhi’s Dakshinpuri suburb. She rarely smiles but speaks in polite, quiet tones. She is very articulate, intelligent young woman, who spends most of her spare time reading books.

Bharti knows she is unwell. She became ill three years ago, when she became violent and started to self-harm.

“I used to hurt myself, because I felt like someone was scaring my soul, someone is scratching me from the inside,” she says.

She was sectioned three years ago after a suicide attempt that was a culmination of long bouts of depression. Soon after she was diagnosed with borderline personality disorder. Doctors say it is due to abuse from non-family member that took place when she was a child.

She is docile and leans tiredly against the wall of her bedroom. Because of her heavy medication, she so clearly lacks lust for life.

“Personally I don’t feel anything, I have no sensations, I am numb and I feel I am outside my own body,” she says.

In Bharti’s neighbourhood of Dakshinpuri, just a few young people continue their education beyond the basic schooling. Most young adults are made to work to support their families.

Bharti too, works an evening shift at a local call center, which according to her, is ‘mind numbingly boring’. She feels saying the same things several times over and over in an hour is soul destroying and doesn’t give her the intellectual stimulus she so clearly craves.

“It is making me more depressed,” she says.

Professionals fear an epidemic

But Bharti can’t leave her job. She has to pay back her hospital bill for her three-month stint at the mental hospital because her parents took a loan to get her proper care she needed. In India, healthcare is mainly private with some provision for the poorest of the society from the state, which rarely includes mental health care.

Mental health care professionals fear an epidemic because life in India is changing from a traditional family – focused to more urban, work-orientated, which can cause burn-outs and rising levels of anxiety.

People are moving away from traditional lifestyle into cities and away from their family units, normally the support network for an individual. At the same time, there are masses of pressure on young people to consume more and rise in their careers.

“Society is getting disconnected, families are less important now. There is increase in people’s stress levels. There is stress with everything, schools, everyday life. But when stress when not managed properly, it leads into mental illness,” says Jhilmil Breckenridge, the Founder and Managing Trustee of Bhor Foundation, a mental health charity, which works with the mentally ill through training.

According to World Health Organisation 7.5 per cent of India’s population of 1.3 billion suffers from mental disorders but the figure could be much higher, due to the hidden nature of the disease. Even many doctors do not recognise it as an illness, Breckenridge says and the stigma attached to mental illness makes families ashamed of the ill or even try to hide the person.

“Patients get dumped in asylums for years and medicated without proper investigation or therapy,” she says.

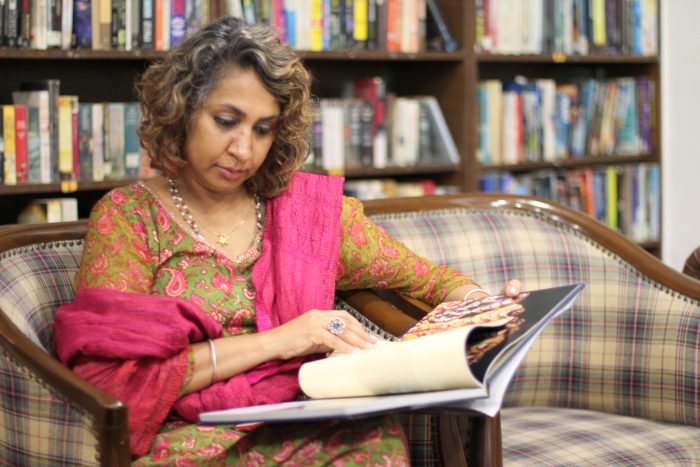

“When stress is not managed properly, it leads into mental illness”, says Jhilmil Breckenridge, the Founder and Managing Trustee of Bhor Foundation. / Photo: Silvija Einola

Learning is a key to mental well-being

The country’s Mental Healthcare Act was passed only this year. It states that every person will have the right to access mental healthcare from services, which are operated or funded by the government. The Act also decriminalized suicide whereas before killing yourself was deemed illegal in India. The Act also aims to eradicate discrimination and spread awareness of mental health.

Whilst activists say it is a step to the right direction, the bill leaves much to be desired. One of the biggest criticism of the new act is the lack of integration policy framework for individuals. There are no tie-ups with vocational institutes, the guidelines do not talk about how rehabilitation is arranged or how patients are encouraged to get back to society.

Adult education could bridge the gap left by the breaking of traditional family structure and it could help individual in finding their place in society.

“People need to belong, they have an intrinsic need to feel important and be useful. Families provided this before but now there are more demands on individual and their performance. Having a creative outlet or engaging in learning something new balances the mind,” says Breckenridge.

“Education is key to mental well-being. It uplifts and invigorates the mind, and gives a sense of purpose for the individual. It should be made more accessible for those recovering from a trauma, depression or even a bad marriage,” says Breckenridge.

Adult education resources vary from state to state

Nevertheless, in India, finding the right kind of course for someone like Bharti is hard. Indian government’s adult learning policy is focused on universal literacy, which tries to provide opportunities for those who had dropped out of formal schooling at some point.

“Adult education depends on the government’s policy, and because the government changes every five years, so does the policy. Right now there is focus on skilling adults and getting them to work rather than supplying them with a higher level education,” says Director of Indian Adult Education Association Dr. S.Y. Shah.

Thus, lot of India’s adult education resources depend on each state’s decisions and actions. For instance in the Southern state of Kerala, which has the highest literacy rate across all of India, adult education centers are well equipped and teachers receive a salary.

The state has a history of education. Initially, educating adults in Kerala was done by Christian missionaries and later the region’s communist party, which still holds the power in the area.

On contrary in the Northern states, such as Delhi, public resources to educate adults are scarce and mostly relying on volunteers or donation – based NGOs.

“Most of the teaching is supplied by voluntary teachers, who have little or no experience in teaching those patients with mental illnesses,” says Dr Shah.

There are plenty of adult education centers run by NGOs but these are mostly focused on basic literacy and numeracy or skills such as sowing or tailoring.

“Due to chronic lack of resources, the support system for those who need it most is missing. India has millions of people who need to learn to read and write and the focus is on those rather than helping those who have a genuine desire to study,” he says.

Advanced learning facilities are scarce. The state-run Indira Gandhi Open University was founded to provide education facilities for those who have no financial means to pursue an ordinary degree or who have dropped out of education all together.

But it’s not ideal for Bharti. She says by the time she comes home from the late night shift at the call center she is too exhausted to open a course book. Her medication is making her unable to concentrate.

Besides her family’s tight budget means Bharti would have to find money for books, course materials and extra tuition. In addition Open University degrees are not always looked upon favourably by employers.

“All I want to do right now is to study”, says 21-year-old Bharti Manoj, who has been suffering from severe mental health problems. /Photo: Silvija Einola

Stigma stays attached to mental health problems

Lack of long-term rehabilitation through education or meaningful training is just one problem India is facing. Mental health has plenty of stigmas attached to it across the country. It is often seen as a shameful for the individual and their family. There just simply isn’t enough knowledge of the illness.

We step outside Bharti’s home but she is reluctant to be seen with foreigners. Dakshinpuri is a tight-knit community of mostly low-caste blue-collar workers where gossiping and hearsay is a way to pass the time. Anything unusual that happens in the community, will soon be known by everyone.

India is a complex country with social layers that determine individual’s behaviour and place in the society. Bharti belongs to a scheduled caste, which is a group of people considered ‘untouchable’ by Hindu scriptures and practices.

Whilst the caste system was abolished over 70 years ago, it still divides people into sections and determines their path in life, including their educational opportunities. People born into scheduled caste are considered socially disadvantaged and in many ways it is hard for them to raise above their social class.

The lower cast or castless are particularly badly taken care of when it comes to mental health because of lack of awareness of the disease.

Bharti says how her community rejected her and she could no longer cope with even distance learning programme that she had tried to enrol in.

“My relatives considered me as a crazy person, and they were embarrassed to be around me. They could not understand the meaning of psychological disorders, even my parents don’t basically understand what is wrong with me,” she says.

“It was hard because everyone knew I was the mentally unbalanced one but no one understands it’s a disease. They just think I am acting crazy,” she says.

Active and creative therapies instead of over medication

Bharti’s story reveals the complexity of India’s alarming problem. Beyond medication and locking up, there are few options available and the country has no sustained effort to help the mentally ill with long-term solutions such as education despite the fact that the disease is on the rise.

“Rather than medication, one of the ways mentally ill patients could benefit is though creative practices, like pottery, writing, painting and other courses. Outside India creative therapies are frequently used to help mental patients, but in India this is still in its infancy,” say Breckenridge.

“Bharti too, is probably over medicated because doctors here tend to do that here and the families don’t question the authority of a white coat,” she adds.

Today Bharti is getting by in a haze, dragging herself through life.

We walk back up to her small room she shares with her younger brother. She sighs heavily as she shares her dream of becoming an academic – a journey that right now looks long way ahead.

“All I want to do right now is to study. Basically my main motive is not to make money or be famous, I want to enhance my intellectual capacities and learn about literature as much as I can. But right now there are no options for me.”

Bharti looks out of the window, her eyes betraying the sadness she carries inside. After a while, she picks up a novel by Dostoyevsky and settles quietly on her bed to read it, seemingly drowning the cacophonic noise of the street outside with her thoughts.

Authors