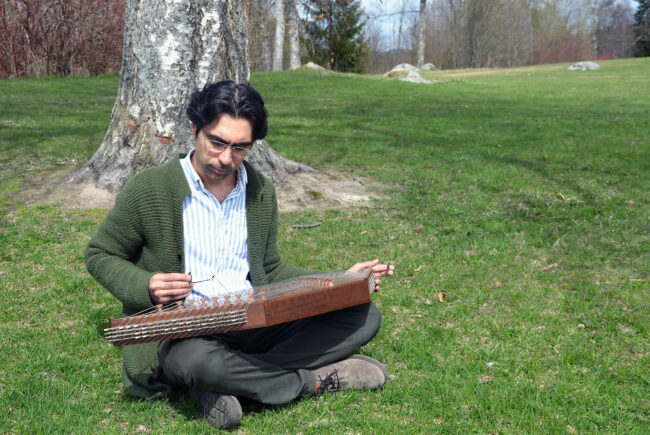

Farshad Sanati plays the santour, an Iranian traditional stringed folk instrument. Photo credit: Katariina Henttonen

Farshad Sanati plays the santour, an Iranian traditional stringed folk instrument. Photo credit: Katariina Henttonen

It takes some courage to embark on a completely new study path as an adult. For Farshad Sanati, following his passion in music also meant moving to a completely new country with a new climate, language and culture.

Farshad Sanati worked for about six years as an engineer for Iran’s national airline. Nothing was wrong, but he longed for something else.

“First I worked as a ground engineer and then as a flight engineer. I had a good salary and my social status was great, but I didn’t enjoy that life,” he says.

Sanati has always had a strong passion and talent for music. He plays the santour, an Iranian traditional stringed folk instrument. While working at IranAir, he also gigged as a musician and taught music to others.

“Sometimes I left my job early to go to a band rehearsal or took a couple of days off for a concert in another city. I often waited the whole working day just to go home and play the santour. I learned to handle these two very different fields,” Sanati tells.

A leap of faith

About five years ago things changed when Sanati found out that in Finland, the University of Jyväskylä was offering an international Master’s degree programme called Music, Mind and Technology.

The programme focuses on contemporary research into music perception and cognition but also looks at different applications of music technology and encourages students to do their own empirical investigation.

When I left Iran, I didn’t have a clear idea about the future, a job or the possibility of continuing my studies.

For Sanati, the programme sounded like an ideal way to follow his passion in music whilst also utilising his earlier education. Together with his girlfriend at the time, Sanati decided that it was the right time to emigrate.

“My girlfriend applied for the University of Jyväskylä first, along with some other universities. I found my programme by chance. It seemed very interesting and unique.”

Sanati left his job, family and country to move to a completely different country with a new climate, language and culture. He now says that the first months in Finland were hard. He was accepted into the programme but had to wait for the official decision for a few months.

“When I left Iran, I didn’t have a clear idea about the future, a job or the possibility of continuing my studies in the new field, but I was determined. I had burned some bridges behind me, so it was not possible to go back to IranAir anymore.”

Applying engineering skills to music

Having studied engineering and being familiar with basic mathematics, physics and computer science greatly helped Sanati with his musicology studies.

The fact that he had also worked in the engineering field made it easier to understand and handle the themes covered, such as signal processing and music information retrieval.

Studying in Jyväskylä has been more diverse than he expected, Sanati says.

“It was hard to choose which topics to concentrate on, since the programme covered so many different research fields from neuroscience to MIR. I was interested in ethnomusicology but felt there was too little research on world music.

MIR refers to the interdisciplinary science of retrieving information from music. According to Sanati, most MIR has traditionally concentrated on western or popular music, not world music.

Now Sanati is working on his Master’s thesis that deals with computational ethnomusicology and Persian folk music. This involves work with MIR that enables analysing vast volumes of research material very quickly using computer technology.

Music as a language and a community

During the difficult early days in Finland, music helped Sanati to cope with uncertainty. He met other musicians after a concert at the local multicultural centre Gloria, became friends with many of them and found a community, with music being their common language.

During the difficult early days in Finland, music helped Sanati to cope with uncertainty.

Sanati played and still plays in different bands from his own Persian folk music group Road Ensemble to a Finnish-Persian fusion band Desert Rain and a mediaeval group Yr Awen. He also teaches the santour to students from different cultures and has given several workshops and lectures about Iranian music all over Finland.

“During these years in Finland, I’ve played more music than I did during thirty years in Iran,” Sanati says.

He is also continuing his career as an engineer in Jyväskylä while working on his thesis, but he wants to push ahead with his doctoral studies in musicology.

“I will apply for the PhD programme and try to get funding. I think it would be too hard to do a PhD and work at the same time.”

Caption: Farshad Sanati was an engineer and a musician in Iran. He moved to Finland to combine the two.

Author