India’s adult education system is focused on the skilled workers offering little or no help to those who have dropped out of education early. However, NGOs step in where the state fails creating opportunities for the most determined ones.

Nazmeen Parveen pulls down her hijab shyly but her eyes reveal a steely determination.

She has one dream in life.

– Since I was a little girl, I wanted to be doctor.

Nazmeen is 24-years old but she seems more mature for her age. When she is being instructed by her teacher, she fixes her gaze on her book, concentrates and tries to read the sentence in English. When she stumbles, she tries again. And again.

–I have a donkey. The donkey takes me to the market. I buy some vegetables, she repeats slowly, her finger tracing each and every word.

She lives nearby in a large Delhi slum with her husband and two small children. She left school at the age of 13 with little skills, barely able to read a few words in Hindi.

– My father became ill, so I had to stay at home to help my mother, she couldn’t have coped otherwise.

Married at the age of 18, she soon became a mother herself and had to take care of her children and home, which meant schooling was not on top of her agenda. In India, children are the focus of the family and it’s always mother’s job to take care of them.

Over the years, she thought of returning back to school many times and the idea of becoming a doctor never went away.

Now her children are old enough to manage a few hours a day with either her husband Hossain or a relative.

When she heard that a local NGO Shanti Sahyog was giving adult reading classes for a couple hours a day, she jumped at the chance.

– It was a big opportunity, I knew I had to do it now, she says smiling and carries on with her reading practice.

Nazmeen and her friend Yasmin are working hard to learn English in a course aimed at the economically disadvantaged. / Photo: Pia Heikkilä

Adult education much needed

Nazmeen’s story has a familiar ring to it all over India. Millions of girls – and boys – drop out of formal education due to poverty or family needs.

Social support from the state is non-existent in India and public services are often very poor, which means getting daily work is the only way to survive. Children as young as five are sent to earn a wage, which means they drop out of formal education.

Education in India is provided by both private and public operators. Most middle class families send their children to fee-paying schools but for the poor there are few options.

India introduced ‘Right to Education’ or RTE in 2009, which states that every child between the ages of 6 and 14 has a fundamental right to education supplied by state schools.

The idea is good but the reality is very different. The state schooling system suffers from chronic underfunding, which means children drop out of school in hope to pick up education later in life or get a placement with the government funded skills programmes. Demand for adult education is huge.

– State school’s education is often seen as poor standard and this is why many lower income families do not see the value in the education it offers but they seek to repair this later in life. The need to educate adults is acute, said Ajay Kumar Associate Professor at the Group of Adult Education, School of Social Sciences at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi.

Adult education one of the most neglected areas

Whilst Nazmeen’s story is one of determination and willpower, not everyone is as lucky as her. The reality is often harsh for those with little or no schooling.

Many state-wide adult education programmes require a minimum of basic schooling and literacy and are focusing on skilling people, especially those who already have entered the workforce. Those with no schooling are often left outside adult education without any public support. The system needs reform badly, researchers say.

– There is very little help on offer for those adults, who have not been able to complete their basic education. It is the most neglected sector within education. Even within higher education institutions, the officials have always undermined their importance and have given only an ad-hoc attention to it. There is a huge need for a system overhaul, says Ajay Kumar.

The Indian government is trying to help people to get back into education with various projects and tie-ups with local NGOs and its own programmes.

One of the longest running state-wide campaigns is National Literacy Mission, which started in 1988 and which aims to educate 80 million adults between the age of 15 – 35 over an eighty-year period.

It is part of the 40 – odd schemes run by the Indian government to help people to get a better skillset. In addition to central government efforts, each one of the country’s 29 states operates a myriad of different adult education programmes, some with the help of a local NGO.

Critics say that these mass literacy campaigns too suffer from inadequate budgetary provision and lack of infrastructure and proper planning.

– The teachers lack commitment, they are ill-trained, lack knowledge and suffer many distractions as a result of multitasking because of bureaucracy and administration work, Kumar says.

The need to educate adults is huge because millions enter adult life without basic schooling. Unesco’s Global Education Monitoring – report says that based on current trends India is expected to achieve universal primary education in 2050, universal lower secondary education in 2060 and universal upper secondary education in 2085.

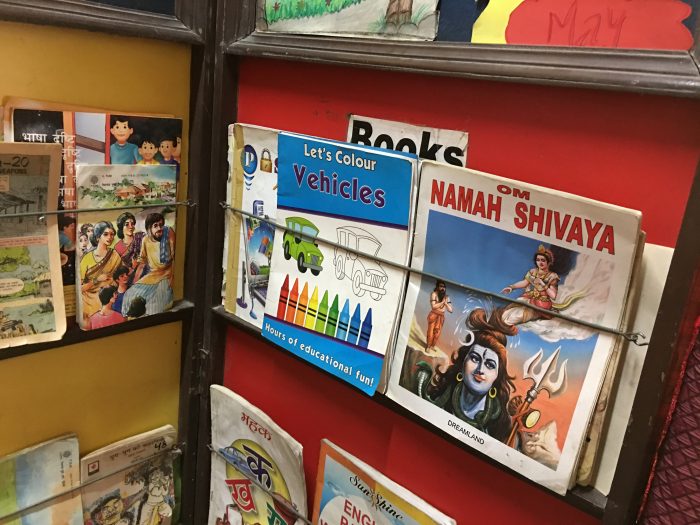

Public resources to educate adults in basic literacy and numeracy are very scarce. / Photo: Pia Heikkilä

Skilling India

India acknowledges that a key challenge to its growth and competitiveness is its inadequate supply of skilled labor due to lack of educational development programmes for adults.

India’s 29 states all have basic autonomy over their education budgets whereas the central government decides on any bigger picture initiatives.

The government has taken action by launching several schemes. The largest, Skill India, was launched by the country’s Prime Minister Nardendra Modi two years ago.

It is an umbrella campaign housing a wide range of initiatives such as National Skill Development Mission, National Policy for Skill Development and Entrepreneurship and the Skill Loan – scheme, which is a loan facility for those wanting to take up an adult education course.

The aim of Skill India is to transform India into a competitive, middle-income country and train over 400 million people with different skills by 2022. The ambitious plan is to train its population to meet the needs of the growing market and create a knowledge economy in India.

Skill India programme is supervised by the Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship and is based on Public Private Partnership, which encourages companies to take up in-house training.

The concept still needs work, researchers say.

– The programme has taken off but it is still in its nascent stage with weak implementation and ready to imbibe old corrupt values and practices rather than to create new values and practices, Kumar says.

The universities and the higher education systems have not been involved and integrated with Skill India, which may hamper its progress.

– The skilling India programme is being loosely coordinated and implemented by a number of government ministries and departments, which makes it the most vulnerable programme, Kumar adds.

In addition Skill India is very focused on those who have already entered the workforce and have basic skills or at least minimum literacy. Leaving the uneducated outside the system poses dangers to the whole society, experts warn.

– Even if India is able to become an economic giant with wide regional disparities, India without a literate and enlightened population will be vulnerable to all kinds of social, political, environmental and governance risks, says Kumar.

NGOs step in when state fails

Lack of sustained and universal provision for literacy training or professional training for those adults with no skills means NGOs are often left to carry the burden.

Any state government has free hands to decide to create an adult education tie up with a local NGO. Thousands of NGOs operating in Delhi are receiving support from the New Delhi Municipal Countil (NDMC).

One such is Shanti Sahyog, where Nazmeen in studying.

However, funding is scarce and resource allocation carefully monitored.

– The local government wants to improve the slum dwellers’ education but funding for our programmes often comes from private donors since public funding is very scarce and not enough, says Dr Suman Khanna Aggarwal, the founder of Shanti Sahyog.

In the patriarchal setting of an Indian family, girls have a lower status and fewer privileges than boys. The fact is that girls are still dropping out of education – even today.

According to the last Census in 2001, male literacy across the country was at 75.26%, while female literacy was 53.67%. Regional differences do exist but the Census gives an accurate picture of what is India today.

More often it is the girl child who gets removed from school by their parents because she can help around the house or earn a wage as a housemaid.

– It’s generally very difficult to get these women out of their homes and come to study because rarely they see a value in the skills provided by education, says Aggarwal.

Thus, adult educators try to focus on helping the women to get the skills they need for modern life such computer training and personal finance.

In addition, the all-female environment at Shanti Sahyog encourages women to attend since traditional families in Delhi’s Kalkaji slum area do not generally allow the women to move alone outside. Having basic literacy and numeracy skills can help the women to move outside the house more confidently.

– When they complete the course, they have learned to read and write, count money in the market and negotiate daily finances, it gives them a strong sense of empowerment, Aggarwal continued.

Government’s Skill India offers little or no help for those lacking the basic reading and writing skills.

– For the uneducated slum dwellers, the central or local government offers little or no support, says Aggarwal.

Women from Delhi’s Kalkaji slum are taking part in vocational training arranged by a local NGO and learning useful skills such as pattern making and sowing. / Photo: Pia Heikkilä

Failures exists in even the voluntary sector

Religion often plays a part in educating adults too. India’s three main religions – Hinduism, Christianity and Islam – all offer support for the poorest members of their communities. But some of the schools run by religious NGOs require their adult students to convert or at least study the religion in order to benefit from the free training they receive.

– This can be problematic because the education comes with a caveat – give up your religion in order to get ahead in life, Dr Suman Khanna Aggarwal notes.

Some NGOs are unable to cope with the lack of funding, which means only about 15% are able to offer adequate support for the adult learners. Their national contribution to the social and development sectors is very low, according to calculations made by the School of Social Sciences at the Jawaharlal Nehru University.

– The remaining NGOs are primarily individual-family based and self-serving for their founding members. Their source of funding is always uncertain and meager. Majority of them do not enjoy the confidence of the public, the government or the donors, Ajay Kumar notes.

Whilst the big picture for India’s adult education may look bleak, there are glimmers of hope that show potential for the future.

One such is Nazmeen’s.

Her two children come to meet her after her class is finished. They squeal with delight as she picks them up, hugs and kisses them and gets ready to say goodbye to her teachers and classmates.

Her teacher says she is progressing well and her reading skills have improved in just few months. She plans to take further classes later in the year.

– I’ll be back tomorrow, ready to learn more. My dream does not seem impossible any more, she says as she takes the hands of her two children and walks out of the class, full of confidence and optimism for the future.

Author